1.0 Introduction

2.0

Montrealís Present Context

3.0

Canadian Historical Setting

4.0

Montreal Historical Setting

5.0 Case Studies:

Endeavors in Urban Agriculture with Various Origins in Montreal

5.1

Jardin Rencontre

5.2

Mountainside

5.3

The Victoria Community Garden

5.4

The NDG Garden Club

5.5

The Cantaloupe Garden

6.0

Comparative Case Studies

6.1

New York City

6.1.1 The Founding of the Green Guerillas

6.1.2 NYC Failed Involvement

6.1.3 NYC Fiscal Crisis and unsuccessful

urban renewal

6.1.4 NYC Motivations for Gardening

6.1.5 Funding

6.1.6 Race Relations and Community Gardening

6.2

San Francisco and SLUG

6.2.1 The Origins of SLUG

6.2.2 Loss of Public Funding

6.2.3 Source of Funding

7.0 Conclusion

8.0

Future Directions

1.0 Introduction Back to top

A community enjoys food security when all people, at all times, have access to nutritious, safe, personally acceptable and culturally appropriate foods, produced in ways that are environmentally sound and socially just. A combination of hunger in Canadian society, continued degradation and loss of agricultural lands, limited economic viability of small and medium sized farms and a general dissatisfaction with the food system in general has propelled community organizations to action.

Part of the vision of moving toward community food security in Canadian cities includes exploring avenues for urban food production. While there is skepticism of the abilities of urban food production to feed cities, evidence is being gathered that great possibility exists for feeding urban populations closer to home.

Individuals and groups envision a variety of strategies to recreate food production systems. Most food production is organized around community and allotment gardening, rooftop gardening, and backyard garden and urban farms. The community food security movement links these efforts together with a comprehensive vision of a just and sustainable food system. To this end, urban agriculture must go beyond merely providing land for people to garden on. It must be driven by principles using gardening as a means to community development through such projects as providing job training, increased food security, self-reliance, training and recreation, inner-city renewal and therapy.

This report examines the evolution of urban agriculture in Montreal and discusses the different systems that have developed within the city over the past thirty years. In particular, we look at the rise of an extensive and well-organized city run gardening program with a comparable lack of socially driven gardens. Our research question examines the effect on the evolution of a strong city run program on the development of socially driven gardens.

This analysis begins with a history of urban agriculture in Canada and Montreal. Case studies of various Montreal gardens are described in order to draw conclusions on the reasons behind Montrealís gardening context. Next, a comparative analysis is made with two cities, New York and San Francisco where informal socially driven garden movements have been very successful. We outline differences between those cities and Montreal in order to understand why a comparable system has not developed here. Finally, commentary is given on future directions on expanding socially driven gardens in Montreal.

2.0 Montrealís Present Context

Urban agriculture can be defined in various ways. Jac Smit defines it as "an industry that produces, processes, and markets food and fuelÖwithin a town, city or metropolis on land and water dispersed throughout the urban and peri-urban area" (Cosgrove 1998: 1). Though this definition focuses on industry, the underlying concept is one of self -sustaining existence in an urban setting. This concept is one of the principal driving social forces underlying large-scale urban gardening movements. A community garden is defined as "an open space that a group of citizens voluntarily manage, where horticultural activities are practiced" (Cosgrove 1998: 2).

The city of Montreal has one of the most well established community gardening programs in the world. The city program, run by the Department of Sports, Recreation, and Social Development, provides the land, water, fencing, tools, as well as various services including garbage pick-up, maintenance, and horticultural animators. The animators are responsible for keeping contact with the various gardens to sort out any problems or provide gardening expertise or clarification of rules. About 2/3 of the gardens are located in parkland zones, which provide them with protection from long-term development.

The Montreal urban community numbers approximately two million people. At least 10,000 of them are involved in gardening and the island hosts around 100 community gardens (Cosgrove 1998: 6). There are also private gardens, which are located on private land and run by privately funded organizations. These gardens can have different rules and motivations, ranging anywhere from promotion of communal living to private leisurely gardening. Montrealís city program has run parallel to some of these organizations and has essentially blended with others.

There are both positive and negative aspects to this city run program. On one hand it provides gardening opportunities to thousands of Montrealers while contributing to the greening of urban spaces. Other cities have less stable land claims than do the gardens in Montreal. On the other hand, the city program, which emphasizes recreational gardening, has replaced socially driven projects. These projects use gardening to alleviate poverty, support an alternative food distribution systems and other and other means of achieving greater local food security. The existence of a well-established city program in Montreal has affected the development of socially driven organizations, which can be seen in their relative scarcity compared to the city run gardens.

3.0 Canadian historical setting

In Canada over the past century there have been about six major waves of community gardening enthusiasm. These fluxes of increased gardening popularity seem to have occurred during times of war and recession. These various movements are reflections of the common social theme for the desire for self-sufficiency and closer proximity to the natural world.

Railway gardens were popular from about 1890 to 1930. These began when the Canadian Pacific Railroad Company (CPR) began using station gardens to promote the fertility of the land in the prairies to encourage settlements. In the east, the public pressured for railway station beautification. The establishment of railway gardens was part of the response (Baeyer 1984:14). This practice carried on through the 1930ís but dwindled in influence with the popularization of other modes of transportation and the drastic post-WWII cultural changes.

The school garden movement began in 1900 and waned by 1913 (Cosgrove 1998: 5). These gardens were present at schools prescribing to the philosophy of the Nature Study movement. The idea was to educate the spirit as well as teaching children to recite facts. Through the process of growing a garden it was hoped that they would develop their own understanding of their surroundings (Baeyer 1984: 37). The movement rapidly diversified, becoming low key with the onset of WWI.

Vacant lot gardens rose up as part of an increasing concern for the urban condition during the interim of the two world wars. The poor and unemployed were provided with food and work opportunities and business increased with the greening of cities (Baeyer 1984: 92).

The World Wars gave way to their own community gardening movements. The Relief Gardens of WWI and the Victory Gardens of WWII were chiefly motivated to supply food for the war effort (Cosgrove 1998: 5)

A general increase in concern for the state of community culture, the environment, energy conservation and self-sufficiency facilitated community garden development from 1965-1979. This has been called the Counter-Culture movement. For example, City Farmer began to publish in 1979 partly as a response to concerns about the OPEC energy crisis, which accentuated peoplesí need to become self-sufficient (Levenston 1981: 1). Many urban gardening programs came into being in the post-OPEC period (including Montrealís). This movement saw that community gardening provided a vehicle by which to address all of these concerns (Cosgrove 1998: 4).

The continued popularity of community gardening

through the 1980ís can be attributed to the most recent movement, the Open

Spaces movement. People in urban areas have recognized that mental health

requires a certain amount of open space and green area. This idea has helped

to carry community gardening through to the next decade (Cosgrove 1998:

5).

Back to top

4.0

Montreal historical setting

There was a two-fold beginning to the Montreal movement. Portuguese and Italian immigrants were gardening in open spaces, so called "guerrilla gardening" in the early 1970ís. They used both public and private open and unused space. The city began to develop a process to regulate these activities, although informal gardening still continues today. The other stream developed when citizens in the Centre-Sud district approached the Botanical Garden with proposals to start gardens in their neighbourhood with city support. Their regulation became progressively more formal as interest began to heighten within various communities to have community gardens. The origin of the movement was thus due to both underground and official gardening initiatives.

The stable status of the city gardening program can be attributed to Pierre Bourque, who was in charge of the Montreal Botanical Garden. He fostered the program until it became too large for the Botanical Garden administration to handle. A thorough review of the program by the City of Montreal took place in 1985, with many implications. Uniform policies on community garden operation and establishment were devised by the city to be implemented by the Department of Recreation and Community Development. This city department worked cooperatively with several other municipal organizations involved in development and urban planning to ensure fair and successful operation of the program (Cosgrove 1994: 2).

5.0 Case Studies: Endeavors in urban agriculture with various origins in Montreal

The majority of Montrealís urban agricultural

movement has been realized through the city run program. There have been

initiatives outside of the cityís jurisdiction on private lands, funded

by private organizations as well. These organizations had various reasons

for implementing the programs, though very few feature social health and

food security being of major concern. The city movement has primarily focused

on gardening as an activity for leisure and recreation. Each urban agricultural

project in the proceeding case studies has been created out of a community

driven desire to garden. A few dedicated groups and individuals came together

to consolidate efforts resulting in the creation of the gardens.

5.1 Jardin Rencontre: A city run community garden

On a bridge over the Decarie highway in NDG, where there used to be a police

parking lot, there is a now a community garden. The city changed the location

of the precinct station leaving behind a paved area, seemingly undesirable

for any use. Helen Sentenne was around during the gardenís early stages

of creation (between 1981 and 1983). That section of NDG did not have a

garden, so the city seized the opportunity to explore the possibility of

creating a community garden on the site. Mrs. Sentenne recalls that the

city began to invite people to submit their names on the basis of interest

in participation. She said that they were charged a small fee and the city

fenced the area, built a cabane, and dug out the plots for the gardeners.

They are currently provided with all of the benefits that the city community gardening program has to offer, such as compost and loose soil. A government sponsored expert in gardening (called an animator) visits occasionally to advise people and answer questions about gardening. There is an annual city sponsored buffet to which the 5 best gardeners from every city garden are invited to receive awards. Pamela Tait, the garden's president, organizes weekly meeting picnics with members and the city animator to keep the garden running smoothly. Mrs. Tait said that the Decarie garden is used by people from the surrounding community as a good excuse to spend time outdoors, get some exercise and to have a supply of fresh vegetables.

This garden provides a comprehensive overview of the advantages that the city program has to offer. By providing gardening infrastructure, materials, horticultural advice and other benefits, the program gives strong support to gardening. This support makes alternative efforts less attractive since the city program is well organized. Also, by and large gardens which are managed by the city are primarily leisure oriented. There is some variation amongst the gardens of the city. However, the actual city program, in its implementation and management, places no emphasis on social issues. This means that socially driven gardens have little room to develop in the Montreal context.

5.2 Mountainside: A city run community garden

Mountainside is Montrealís newest city managed

garden, having begun its first season in spring 1999. Located in a Cote-des-Neiges

neighbourhood with a large ethnic community, the users are mostly South

Asian immigrants in their middle ages.

The garden came about through the efforts of a local CLSC worker, Denise LeBlanc. This woman was also the head of a group called Promis whose purpose was to help recently arrived immigrants integrate into society through activities and by providing advice. Four years ago she noticed that many families had balcony gardens outside their apartments and that many people expressed an interest in gardening. Familiar with the cityís program, she suggested people form a committee and apply to the city for a community garden. Three years later, a 24-plot garden was established on local parkland.

Mountainside is typical of the services and goods that the city supplies to its gardens. The city absorbed the cost of establishing the garden. It provides all the necessary infrastructure including a fence, a cabane for tools and wood for plot borders. It also supplies water and electricity. Furthermore, a horticultural animator makes regular visits and provides advice to the gardeners. The garden has a long-term, five-year lease and is fully protected due to its zoning as parkland. In addition, the garden must adhere to city rules on decision-making, plot allocation and growing regulations.

Mountainside serves as an example of what has become of informal gardening efforts since the 1970s. Gardening efforts are drawn to the city-supported program as opposed to the spontaneous gardens like those of immigrant communities after World War II. Mountainside demonstrates the attractiveness of the city program due to the security of the land offered by park zoning. It is an interesting case where motivations of social integration have been blended with the city program. However, the emphasis in the garden, through the cityís rules, is primarily for leisure.

5.3 The Victoria

Community Garden: A privately owned and operated community garden

In 1973, around the time that the city run program was just getting on its feet, the Golden Age Association and the Jewish General Hospital created a community garden though a joint effort (Guggenheim: pers.com.). Some members of the Golden Age took notice of the unused land that belonged to the hospital and received their permission to clear the land for use as a garden. They received a grant from the federal government and the city supplied them with a gardening manual, a water supply, stones for walkways, and tables and benches (Guggenhiem: pers.com.). The garden has its own sub-committee in the Golden Age Association, which supplies the group with a meeting place and a small monetary contribution. The gardeners also rent their plots for a minimal fee. The revenue goes to the purchase of essential tools and funds community picnics. When the garden was first founded there were approximately 200 gardeners, mostly from the Jewish senior community. It was intended for people of 55 years and over (Guggenheim: pers.com.). Currently, the garden is well known as the second largest garden on the island and the most ethnically diverse.

Pierette Elfstrom, the Victoria Garden president, said that there are only a few of the original gardeners left. There has been concern expressed about the long-term status of this garden as it has been established on private land. Pierette Elfstrom, the garden president said that the number of plots has decreased over the years as the hospital has had the need to expand and develop. There used to be 161 plots and now they are down to 141. This poses a looming threat seeing that it is currently the second largest garden on the island, is completely full, and has a waiting list (Elfstrom: pers.com.).

This example shows how gardens created independently of the city program can also be very similar to it in respect to their management, structure and organization. Victoria at the same time demonstrates the problem with gardens that are not protected by the city. Eventually, expansion and development will continue to shrink the garden until it is gone.

5.4 The NDG Garden Club: A private gardening club on private land

The history of this club dates back to WWII during

the Victory Garden Era. At that time there were over 100 gardens in the

area from Cote St. Luke to Somerland. The club was founded in 1957, when

the gardens were no longer being used for the war effort and thus has been

in existence for over 40 years (Ferriero 1999: 1). As opposed to the city

run gardens, this club has their own president and a constitution, which

was established in 1968. Membership in this garden is somewhat exclusive

because the group does not advertise and are choosy in the selection process.

A car is usually required to get to the plots, which further narrows the

scope of membership (Ferriero 1999: 3).

The continual threat of development for privately owned community gardening spaces seems also to be relevant to the NDG garden club case. Back during the time of the clubís founding, they had to be relocated from the old victory garden spaces because of developing plans for a school and a swimming pool in Cote St. Luke. Complaints to the city had no effect on their fate. Since then the club has had three sponsors, the Julius Richardson Hospital, the Montreal Blind Association, and the Salvation Army, which supplied three different plots of land to them for gardening. The Montreal Blind Association provided them with land in 1964, which it built on a few years later. The Julius Richardson Hospital supplied a gardening site in 1973, which was federally funded as a part of a senior citizens project called New Horizons. The Salvation Army provided land for gardening in 1980, but the land was first threatened by development and now has been sold. Mayor Bourque promised to relocate this portion of the garden club (Ferriero 1999: 2). However, recent developments suggest that the garden will be completely lost.

This garden is yet another example of the continual threat of development to privately run gardens. It also shows that privately run gardens can have diverse forms of management and policies, as opposed to those overseen by the city.

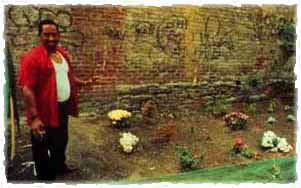

5.5 The Cantaloupe Garden: A privately owned and operated communal garden

Cantaloupe was established in 1997 by the NDG

environmental group Eco-Initiatives. It was founded in partnership with

numerous community groups such as the YMCA, on whose land the garden is

located. Its goal is to use gardening as a means of social reinsertion

of marginalized people such as single parents, recent immigrants and low-income

earners. Participants and animators garden collectively, taking the produce

that they need and sending the surplus to the local food depot. The garden

recently produced over two tones of food while involving dozens of people

in its project.

Cantaloupeís success has come despite certain challenges which may have discouraged a more general adoption of socially driven gardens in Montreal. First, funding for the garden had to be obtained through grants, a much less certain prospect than city support. Second, the garden is located on private land that has less guarantee of security than the park zones that many city gardens lie on. Third, a project that seeks to promote food security requires a network of community groups working together. This kind of organization is complex and depends on building organic relationships, as opposed to the institutional bureaucracy of the city.

These case studies are intended to provide a comprehensive feel for the diversity of urban gardening projects that have been in existence in Montreal. They each have drawbacks and benefits stemming from their forms of origin. Some are exclusive, some all-inclusive and educational, some have land security and others are certainly threatened. Some follow their own mandates, others have to follow the city mandates, and yet others have modeled after the city mandate but on private land. The bottom line is that security of land and a sense of community are the two main elements involved in community gardening. The city program provides the permanence of the land, while the sense of community comes from diverse sources contingent upon the group of origin. These advantages have affected the development of other types of garden, and resulted in a comparative lack of socially driven gardens.

Montrealís situation can be contrasted with examples

from other North American cities, such as New York and San Francisco, where

spontaneous, informal, and socially driven garden movements have been very

successful. These cities feature large, well organized not-for-profit groups

dedicated to facilitating gardeners while maintaining principles such as

integrating marginalized people and providing skills training. The case

studies identify factors particular to these cities that allowed the development

of socially driven systems, and reasons why Montreal has not experienced

a similar phenomenon.

New York City has more than 1000 community gardens, by far the most extensive system in North America. Many of these gardens have arisen through the efforts of community organizations without direct support from the municipality. Furthermore, many of the gardens have been motivated by socially driven goals that go beyond mere leisure activities. The following section examines a non-profit community group, the Green Guerillas, who offer extensive support to community gardening efforts in the city.

6.1.1 Founding

of the Green Guerillas

For community activism to occur, local residents must be organized. The first task is for them to recognize that they share problems or goals. Then they often need to learn methods for attaining their goals. In New York City, the Green Guerillas offer such organization to local people.

The site of what is generally recognized as the first community garden in the Lower East Side was a fenced lot, owned by the city, on the corner of Houston Street and the Bowery. In 1973 a group of thirty or so self described "Peace Corps-Types from the post flower power generationí who later called themselves the Green Guerillas threw balloons filled with seeds and bulbs over the fence onto the lot until the group finally received permission from the city to garden. Working with local residents who were tired of the disinterest in and destruction of their community, they cleaned and greened a vacant lot in an area known for its urban blight. Other residents were inspired to start their own gardens, and the Green Guerillas incorporated as a not for profit organization, with the goal of teaching low income New Yorkers the art of city gardening (Keller 1990:136).

Very early the membership decided that the organization itself would stop doing any actual gardening. The agenda has become one of facilitating self-sufficient gardens by teaching gardeners technical and organizational skills, both horticultural and political, and by supplying them with free garden materials that the Green Guerillas obtain by seeking donations from anybody who may have surplus supplies or money. The criterion for receiving this aid is that it must be requested by the gardeners and the garden must be on publicly accessible sites. The group does not discriminate between leased and squatter gardens. The group works primarily through over 300 volunteers who come from all walks of life. They work with an average of two hundred community groups each year, and these groups represent community gardens, elderly housing projects, the homeless, schools, and block associations (Schmelzkopf 1996: 154).

The Green Guerillas are a very successful operation, allowing hundreds of private gardens to operate while maintaining a strong motivation of community and social integration. The lack of a comparable organization in Montreal can be partially attributed to the difference in conditions in the two cities, several of which are outlined below.

NYC became involved in urban gardening in 1976, when 3.6 million was spent on designing and building gardens throughout the city as an interim use for vacant land awaiting construction. But the gardens were vandalized and abandoned in short order. Residents asserted that the primary reason for their destruction was that the city failed to consult or include them in the design and building of these gardens, which meant that the people responsible for them had no proprietary interest in the sites.

In 1978, recognizing the success of grassroots neighborhood revitalization programs and responding to the growing number of requests for leases by people who wanted to garden on the recently abandoned property, the city created Operation Green Thumb, a program dedicated to supporting gardeners rather than to building gardens. OGT is one of the few, and by far the largest, city run gardening programs in the US, with federal funding. It leases vacant city property 1$/month, sponsors workshops to teach horticulture, garden design, and maintenance, and it dispenses some soil, plants, seeds, bulbs, tools and other gardening materials (Keller 1990: 128).

NYC involvement can be contrasted with that of the City of Montreal. City officials in Montreal were responding directly to demands of citizens in their involvement with gardens. They always emphasized that they had a partnership with citizens, and this policy ensured the continuation of the gardens after implementation. Also, the failure of NYCís involvement with gardens and its present smaller scale support left a vacuum that motivated the Green Guerillas to fill it with their own efforts. A lack of institutional support left the opportunity for other groups with socially driven goals to take leadership in the city.

6.1.3

NYC Fiscal Crisis and unsuccessful urban renewal

New York City was severely affected by a fiscal crisis during the 1970s. Funds for public services, such as police, fire fighting, sanitation and recreation were cut by more than 30 percent. Disinvestment followed, as landlords abandoned properties and as banks and insurance companies withdrew investments. Because of foreclosures resulting from nonpayment of taxes, much of this property reverted to city ownership. More than 3400 units of housing were demolished, and at least 70 percent of the population was displaced (Ferguson 1992; 117). Some of the buildings were destroyed by arson; others were leveled by the city. The vacant lots became open space, a resource for the urban gardeners. Hence, large amounts of private and public land became easily accessible to people, much of which was in poor areas where people could most profit from gardens. Montreal, on the other hand, did not experience this phenomenon of inner city depopulation and demolition. In the 1970s, land was available but was primarily public land in the hands of the city. This fact may have made spontaneous creations of gardens more limited in Montreal.

6.1.4 NYC motivations

for gardening

NYC and Montreal share different social contexts

for gardening. In NYC, the incentive for gardening is compelling: people

see how other lots have been wrenched away from drug dealers and, for better

or worse, from the homeless. Many garden participants have described lots

that have been transformed from junk-laden spaces complete with hypodermic

needles, empty crack vials, and rusting appliances into productive places

full of color, camaraderie and safety (Schmelzkopf 1996:163). With high

levels of poverty and crime, community gardens in some areas of NYC may

have had motivations that do not occur in Montreal. Urban reclamation and

its social goals may be less of a factor in Montreal than NYC.

The funding for the nonprofit organizations that

support community gardening in NYC comes in part from foundations which

do not exist at the same scale in Montreal. For example, in 1986 the Green

Guerillas gave away over $100 000 worth of plant material to community

gardens. These plants and soil came from corporations such as The Rockefeller

Centre (Keller 1990:125). Nonprofit groups in Montreal can not appeal for

the same type of funding available in the U.S., and public grants are a

major component of Montreal gardening initiatives.

6.1.6 Race relations and

Community Gardens

Back to top

Non profit organizations note that 90% of OGT and Green Guerillas are white, and racial and class difference can be an issue. To offset resentments, OFT and the not for profit organizations continue to promote self determination on the part of the gardeners in terms of administration, everyday decision-making and the actual creation of the gardens (Schmelzkopf 1996:149). One major consequence is that OGT gardeners tend to be much more self-reliant and less dependent on city resources than are community gardeners in other cities (Stone 1992: 174). Hence, the issue of race relations allows more independence in terms of the social motivations of gardens in NYC. Montreal does not have comparable conflicts in terms of race, and so has avoided this type of separation. The City of Montreal maintains strict control over rules of organization of its gardens.

San

Francisco is another example of a city with a strong community garden movement

with socially driven motivations. Municipal involvement is secondary to

the support given by the community-based San Francisco League of Urban

Gardeners (SLUG). This section examines the evolution of SLUG and contrasts

it with the Montreal context.

San

Francisco is another example of a city with a strong community garden movement

with socially driven motivations. Municipal involvement is secondary to

the support given by the community-based San Francisco League of Urban

Gardeners (SLUG). This section examines the evolution of SLUG and contrasts

it with the Montreal context.

One of the USís largest urban-gardening programs and arguably one of its most creative, SLUG is not only responsible for some 100 neighbourhood gardens all over San Francisco, but it has also added on strong economic development and job training components and is rapidly coming up with more. An economic force in its own right, SLUG has a staff of 30-half of them full time- plus 25 garden crew workers and at least 70 young people who draw pay for 10 hours a week while they learn. Its $1.6 million annual budget comes from grants and contracts with the city Recreation and Parks Department to run its 40 urban gardens (Ferguson 1992: 148).

Since its inception, SLUG has added economic development, job training, education and social justice components to its earlier sole emphasis on fostering the preservation and development of community gardens in the city. Its mission statement makes reference to empowering communities and individuals and promoting social justice and ecological sustainability (Aprin 1994: 89).

SLUG seeks to improve quality of life through urban gardening by constructing and maintaining community gardens and urban landscapes, offering horticulture education in schools and communities, conducting youth programs that emphasize giving job and leadership skills to low income groups and serves as a vehicle for involving residents of low income communities in developing small business management and entrepreneurial skills. For example, urban Herbals produces organic jams and vinegar with ingredients grown by SLUG youth and local farmers (Stone 1992: 173).

The program began 13 years ago, when the death

of a federal jobs program left a core of organizers who had held community

gardening jobs without an income. They organized SLUG as a non-profit community

organization to carry on the projects that they already had underway. Thus,

San Francisco had a reserve of skilled people motivated to carry on community

gardening without public funding. Their efforts eventually evolved into

a successful socially driven garden program. Montreal, on the other hand,

has maintained city support for its gardens and so not many organizations

have arisen to fill the gaps (Ferguson 1992:145).

SLUG presently depends partially on private grants from large foundations. Its success has drawn attention from senators and millionaire philanthropists. As with New York, the scale of private funding far outweighs that available in Montreal.

The City of Montreal has developed and supported one of the most extensive community gardening programs in North America. However, this effort, while impressive, has not been matched with development of socially driven gardens that may have greater implications for food security. The city program remains very much leisure oriented.

The fact that Montrealís program is so strong draws most gardening efforts to fall under its wing. People motivated to start a garden look to extensive support that the city offers, and also adopt their rules and regulations on the management of their gardens. Also, informal gardening efforts have blended with the city program, with many gardens that started independently having adopted the city program in return for support. Private efforts continue to be hindered by a lack of security of land, as opposed to the protection offered by city park zoning. Montreal has recently seen the implementation of a socially driven garden in NDG that has been successful despite the challenges against it. However, it remains an exception within the context of the Montreal city program.

Other North American Cities, such as New York and San Francisco, have developed strong socially driven garden movements. Differences in conditions between these cities and Montreal can partially explain why a similar movement has not arisen here. Failure of city support and more access to private funding are two reasons why New York and San Francisco have had a better opportunity to develop their successful systems.

From this discussion there are two broad options for those interested in expanding socially driven gardens within the Montreal context. First, people can concentrate on direct establishment of new gardens. This option faces all the challenges mention earlier. However, with the creation of collective gardens in NDG there is now a successful model to emulate in the city. In fact, Plateau Mont-Royal environmental group, Eco-Action, is undertaking development of a collective garden project involving ecological responsibility and involvement of marginalized people. Partially inspired by the Eco-Initiatives example, they plan to establish pilot gardens next year. With further visible examples available and increased coordination between groups, socially driven gardens will become more viable.

Another area of effort could be reform of the

existing city gardening program. Selected gardens within the most needed

areas, those with low-income populations, could be adopted to incorporate

a more socially driven system. Also, increased cooperation with community

groups could be encouraged. This option faces the challenge of a general

unwillingness to change from within the garden system. Ironically, what

appears to impress city garden administrators most is not our own example

of a socially driven garden, but rather examples from other cities which

are discussed at conferences. Activists might do best to persuade the city

by drawing on both the new Montreal examples as well as the most pertinent

projects from other cities.

Aprin, A. 1994. The Granite Garden: Urban Nature

and Human Design. New York:

Basic Books.

Baeyer, Edwinna. 1984. Rhetoric and Roses: A History of Canadian Gardening 1900- 1930. Fitzhenry & Whiteside Limited. Markham, Ontario.

Confortate, Michel. Interview. November 13, 1999.

Cosgrove, Sean. 1998. Community Gardening in Major Canadian Cities: Toronto,

Montreal, and Vancouver Compared. City Farmer.

Cosgrove, Sean. 1994. Montrealís Community Gardening Program. City Farmer.

Elfstrom, Pierette. Interview. November 11th 1999.

Ferguson, F. 1992. Urban Agriculture for Sustainable

Cities. Environment and

Urbanization, Vol. 4, No.2, 141-152.

Ferriero, Nicolina. Sept.1999. A Report on the

History of the NDG Garden Club: Past

and Present. For Eco-Initiatives NDG.

Guggenheim, Michael. Interview. November 11th 1999.

Keller, T. 1990. The Greening of the Big Apple.

In Green Cities.

David Gordon (ed),

130-145. Montreal: Black Rose Books.

LeBlanc, Denise. Interview. November 11, 1999.

Levenston, Michael. The Early Years at City Farmer

1978-1981. City Farmer.

1981.

Pednault, Andre. Interview. November 3, 1999.

Schmelzkopf, K. 1996. Urban Community Gardens

as Contested Space. Geographical

Review, 85(3), 364-381.

Sentenne, Helen. Interview. November 25th 1999.

Stone, J. 1992. Food Production and Urban Areas. Geographical Review, 80(2), 78-95.

Tait, Pamela. Interview. November 9th

1999.